Benchmarking predictive models

Eduardo Ariño de la Rubia2020-04-14 | 13 min read

It's been said that debugging is harder than programming. If we, as data scientists, are developing models ("programming") at the limits of our understanding, then we're probably not smart enough to validate those models (“debug”) effectively.

There's a bewildering amount of predictive modeling techniques and software libraries available to us building models. As a result, we're likely to end up with multiple models in the course of attempting to solving a single problem. It's important to understand the performance of these models, and provide some measure of confidence regarding which of them will achieve the business objectives of the modeling exercise. That's where benchmarking comes in.

Benchmarks will always be incomplete and partial, but if we are careful, they will be directionally correct: Correct enough that we can make the right choices, and in so doing, make our organizations smarter, more efficient, and more driven by insights.

Benchmarking machine learning models specifically is a challenging endeavor. Even simple changes in usage, software libraries, hyperparameter tuning or compute environment can cause drastic changes in behavior. In this article we will outline the best practices for comparing machine learning models, executing benchmarks, and ensuring that experiments are reproducible.

Benchmarking and system characteristics

While it is important to benchmark the predictive performance of a machine learning model, there are also important operational constraints that require consideration. These include the training and runtime performance characteristics of a model. That is, how long it takes to train a model, how long it takes to score new data, and the compute resources required to accomplish both of these.

Benchmarking operational characteristics may often be as important as evaluating the predictive characteristics of a model. For example, consider the problem of real-time bidding on an ad-buying network. The total latency budget for a bid, covering network access, database queries and prediction, is 100ms. The 80ms spent on calculating a prediction in a deep learning model may mean that the model does not meet the business requirements. A logistic regression model, which returns a result in 5ms, may be more suitable, despite the deep learning model’s increased predictive power. A benchmark that only focuses on the predictive performance of a model would ignore this important aspect of putting a model into production.

The experimental environment

Benchmarking requires that experiments be comparable, measurable, and reproducible. With so many potential combinations of data, predictive modeling techniques, software, and hyperparameters, how a data scientist approaches the experimental environment is important.

Containers offer a framework for executing multiple runs of a modeling or scoring procedure, all with exactly the same experimental setup. This allows the data scientist to use aggregation and averaging to develop a more robust statistic on a desired attribute. Aspects of the experiment can also be incrementally altered in a controlled manner. With the right compute hardware, multiple simultaneous experiments can be run, significantly reducing the time to iterate. Beyond evaluating predictive power, many container technologies provide tools for recording the operational characteristics of training a model and running predictions. These include memory used, storage IO performance, and CPU utilization.

Oftentimes, machine learning models will behave differently given variations in the environment. For example, models that rely on matrix calculations will perform differently when the number of available CPU cores, GPUs, or available system memory is altered. So too if underlying BLAS libraries, such as OpenBLAS, Atlas, or the Intel MKL, are interchanged.

Containers allow the data scientist to test multiple benchmark configurations, all with different assumptions baked into the compute environment, and to do so in a reproducible manner.

Many of the underlying technologies used by machine learning libraries can distort experimental results if misconfigured or used inappropriately. Frequently misunderstood is where and how parallelism may manifest in the machine learning software stack. Many BLAS and other math libraries can take advantage of multi-core CPUs, if suitably configured. If care is not taken to ensure all BLAS library candidates are configured for multi-threading, benchmark results will be misleading.

Similarly, experimenting with strategies for parallelizing resampling at the model-level, for example, may result in an oversubscription of threads-of-operation to CPU cores if the underlying BLAS library is itself configured for multi-threading. The result may be severely degraded runtime performance.

The underlying hardware on which benchmark tests are run should be considered when designing experiments. As opposed to running experiments directly on dedicated hardware, benchmarking may be conducted on shared, virtualized resources such as Amazon Web Services or a private cloud in a corporate data center.

While access to large numbers of powerful CPUs and near-infinite storage may be convenient, the nature of shared compute, network and disk IO resources require that the experiment be constructed with some thought.

Benchmark processes may need to be run multiple times, with an aggregate smoothed measure, such as a median value, used for comparison.

Setting a seed

It’s worth repeating that per the scientific method, benchmarks should be reproducible. Many machine learning models utilize entropy from a random number generator to prime the search of a solution space.

So too do libraries that automate the splitting of train, holdout, test datasets. For benchmarking purposes, these random numbers need to be consistent across all runs. Most random number generators support setting a seed, which serves this purpose. In R this is done with set.seed and in Python, random.seed from the random package is used.

Picking a dataset

It is important to ensure that the dataset used to benchmark machine learning algorithms be representative of the data the model will encounter in production and remains so through the data pipeline. Any biases introduced in the data collection or transformation process may result in selecting a model that performs poorly in production.

Often, errors of this kind are introduced into the pipeline inadvertently. If the data originally resided in a relational database, for example, care should be taken not to sample from a pre-filtered source. For example, the data ingestion processes into the analytical database from which the sample is drawn may have had outliers or records removed to mitigate encoding errors or to meet business rules.

It is important that the benchmark contain the unfiltered data in both the training and test sets. Benchmarking the behavior of a model after all data has gone through a non-representative cleaning process may result in poor real-world performance.

Dataset leakage is one of the most insidious ways in which a benchmark can provide misleading results. If more complex models such as gradient-boosted machines, random forests, or deep neural networks are trained on a dataset with leakage, they may perform better on a holdout set than a simpler model. This despite not providing any greater predictive power on production data.

In effect, the more complex model may have a greater capacity to overfit on a leaked trend which will not be present during actual use. An example of how this kind of leakage can be introduced in a benchmark dataset is the use of improper test/train splits. Given a time series dataset, using a naive test/train split, without taking into account the time series itself, may introduce leakage.

In attempting to determine potential manufacturer quality defects, care should be taken to exclude data after the date that the manufacturer was notified of a quality issue. Predictors for this data may have encoded some latent aspects of the quality defects, such as lot numbers or part types, which may unduly influence models in an asymmetric way. Complex models may be more or less robust to this leakage than simple models, and result in behavior in which the benchmark does not reflect actual behavior in production.

Benchmarking an appropriate metric

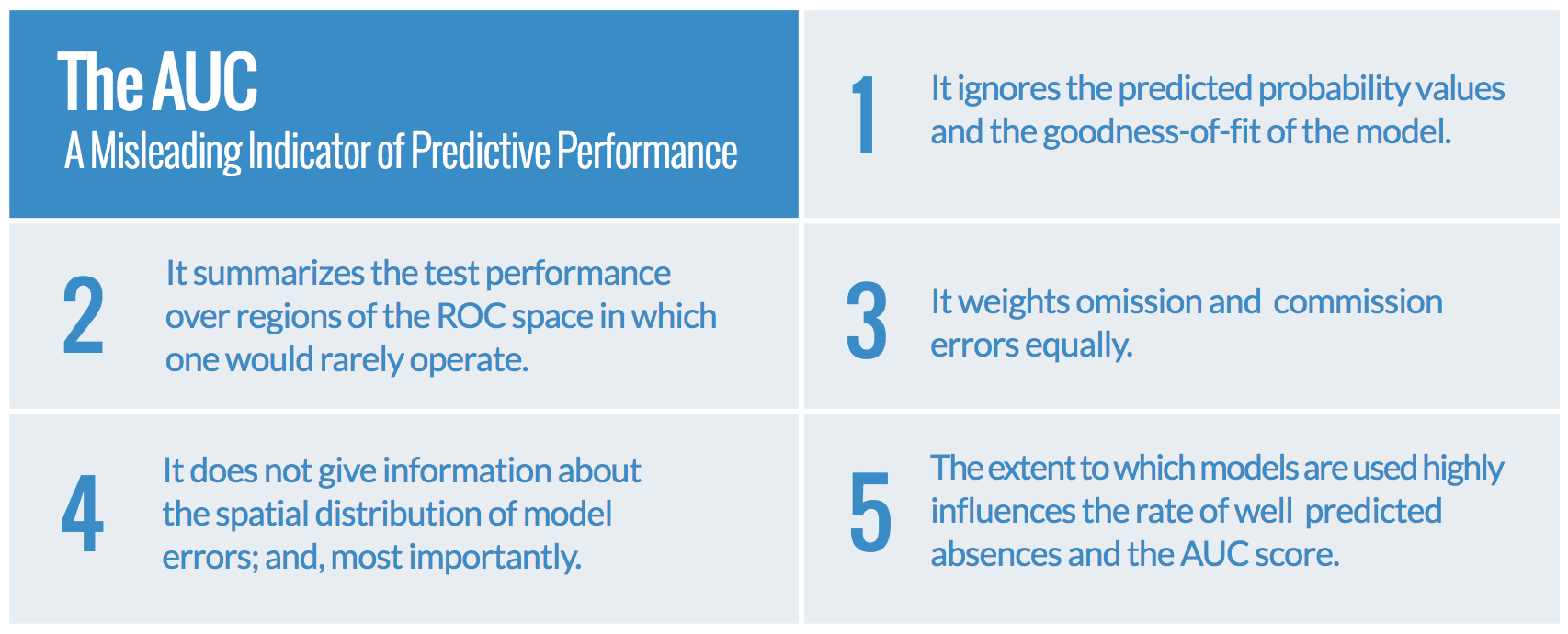

A mistake that is often made in benchmarking is to test and optimize a metric that does not solve the business problem. For example, in fraud detection and medical diagnostics, a false negative may potentially be many times more expensive (or deadly) than a false positive. Benchmarking using the AUC may lead to some very misleading results. The AUC summarizes the predictive power of a model across all thresholds, whereas in production the model will only be predicting with a single threshold. In AUC: a misleading measure of the performance of predictive distribution models, the authors provide five reasons why the AUC is a potentially bad metric for assessing the predictive power of a model.

For many machine learning problems, the AUC is a weak, and often misleading, indicator of real-world predictive performance.

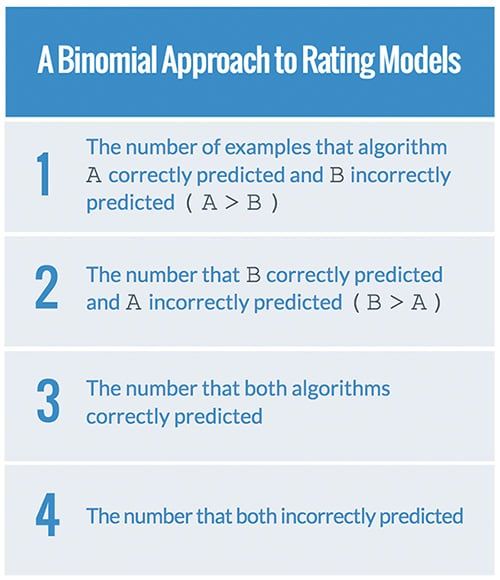

It is important, therefore, not to rely solely on metrics such as the AUC, but rather select a metric which more accurately addresses the true impact of the behavior of a model in production. In On Comparing Classifiers: Pitfalls to Avoid and a Recommended Approach (PDF), Salzberg suggests that data scientists should use a binomial test to rate two different models against each other. The specifics of the test are outside of the scope of this document, but the paper is a worthwhile read for anyone planning on comparing different classifiers, and models, against each other.

Creating a good baseline

In a Quora answer, Peter Skomoroch states that it is often valuable to compare model improvement over a simplified baseline model such as a kNN or Naive Bayes for categorical data, or the EWMA of a value in time series data. These baselines provide an understanding of the possible predictive power of a dataset.

The models often require far less time and compute power to train and predict, making them a useful cross-check as to the viability of an answer. Neither kNN nor Naive Bayes models are likely to capture complex interactions. They will, however, provide a reasonable estimate of the minimum bound of predictive capabilities of a benchmarked model.

Additionally, this exercise provides the opportunity to test the benchmarking pipeline. It is important that benchmark pipelines provide stable results for a model with understood performance characteristics. A kNN or a Naive Bayes on the raw dataset, or minimally manipulated with column centering or scaling, will often provide a weak, but adequate learner, with characteristics that are useful for the purposes of comparison. The characteristics of more complex models may be less understood and prove challenging.

Conclusion

With the large number of modeling techniques and software libraries available to data scientists, it is tempting to develop a small set of “go-to” algorithms and tools, without holistically evaluating the merits of a larger universe of models. This creates the risk of settling on a suboptimal solution—one that may not be capable of being operationalized, may result in lost revenue, and even endanger lives.pre

In this article we explored a number of best practices for effectively benchmarking models: The experimental environment, data management, selecting appropriate metrics, and looking beyond predictive characteristics to how a model might be used in production.

We hope this is helpful in constructing a careful, methodical, and efficient approach to benchmarking models to deliver on the mission of data science: Helping people and organizations make better decisions through data.

Eduardo Ariño de la Rubia is a lifelong technologist with a passion for data science who thrives on effectively communicating data-driven insights throughout an organization. A student of negotiation, conflict resolution, and peace building, Ed is focused on building tools that help humans work with humans to create insights for humans.